Gorillas in Our Midst

In the book, The Invisible Gorilla, co-authored by Christopher Chabris and Daniel Simons, the authors describe many ways that our perceptions don’t always align with reality. The experiment for which the book is named, asked people watching a video to count the number of times players dressed in white passed a basketball to those dressed in black. About half of those viewing the video failed to notice a person in a gorilla suit walking in and out of the scene thumping its chest. Simons notes, “A lot of people seem to take the message of our original gorilla study to be that people don’t pay enough attention to what is happening around them, and that by paying more attention and ‘expecting the unexpected,’ we will be able to notice anything important.”

In a follow up experiment, video watchers knowing about the gorilla beforehand did not improve their chances of detecting other unexpected events. Only 17 percent of those who were familiar with the old video noticed one or both of the other unexpected events in the new video. In comparison, 29 percent of those who knew nothing of the old video spotted one of the other unexpected events in the new video. “The new experiment shows that even when people know that they are doing a task in which an unexpected thing might happen, that doesn’t suddenly help them notice other unexpected things.” Once people find the first thing they’re looking for, “they often don’t notice other things,” Simons said. “Our intuitions about what we will and won’t notice are often mistaken.”

Selective perception is not just limited to the visual. Life is complicated, and we often rely on experts, especially those who project a high level of confidence, to guide our decisions. In the illusion of confidence, we assume that self-assured people are competent people. Studies in the book show, however, that “the confidence that people project, whether they are diagnosing a patient, making decisions about foreign policy, or testifying in court” is no guarantee that they are as well-informed as they believe.

The book also points out other illusions we subscribe to: memory, knowledge, cause, and potential. Knowing that these illusions exist can help us form a better understanding of the world around us.

Certainly a review of this book, written in 2009, is relevant in today’s COVID-19 environment. Most of us were focused on who was passing the ball, and not on the potential for a gorilla to enter the scene. Experts perhaps sounded the alarm about the potential for a pandemic, but emergency management requires preparation for all sorts of potential emergencies – a terror attack, a flood, earthquake, etc. Full focus on total preparedness for any and all ‘black swan’ events requires a financial and attentional level of commitment that few have the wherewithal to accomplish.

So what’s next? Yes we can learn from past mistakes in order to be better prepared, but life is full of sudden emergencies. Over-reliance on experts can do nearly as much harm as good. The experts at Imperial College predicted 2 million deaths. Experts at the CDC recommend wearing masks, while the Surgeon General advises against them. Experts in Sweden drew different conclusions than the experts in the US. While weather forecasting has greatly improved in accuracy in the last 50 years, anyone who’s planned an outdoor event knows that experts can be wrong.

Experts are one voice, but critical thinking is an essential component to solving problems, and effective problem solving begins with asking questions. These questions help us get to the root of the matter and determine what does or doesn’t make sense. Logic is crucial to critical thinking. But it can never take full account of the emotional human factor affecting how we see and respond to problems.

In numerous articles and stories about those companies who have adapted or pivoted in response to the pandemic, decisions will have to be made about which changes will become a more permanent part of our lives. I’ve read dozens of articles from authoritative sources (experts) who are brave enough to try to paint a picture of our what will be our new reality:

- Telehealth is being touted as a path to true healthcare reform. A video visit, with accompanying technology saves the patient from potential exposure, and a trip to the office, especially for the elderly or those in remote rural areas. But would you like to get a cancer diagnosis through a video screen?

- Bars are lobbying for a further extension of laws allowing the sale of cocktails to go, and Zoom happy hours have replaced the in person event. But online gatherings remove the possibility of a chance meeting with an old friend, an unexpected conversation with a stranger, or the sense of camaraderie of cheering on our favorite sports team.

- A flurry of app developers are working on or promoting contact tracing solutions, which can provide valuable information to researchers and public health officials. But as Matthew Pjecha from the Center for Practical Bioethics points out, failure to account for unintended adverse uses of personal data is a big risk, and trust is essential and sorely lacking, especially in marginalized communities.

- Architects, commercial building owners, and companies are all seeking to determine what ‘re-opening’ looks like in the offices of the future. Some suggest a larger footprint, to allow for more distancing, while others point to an increasing telework phenomenon leading to smaller building footprints. Some employees are savoring the opportunity to work from home, while others can’t wait to return to the office. Building leases tend to be long term, but shifts in how and where work gets done are likely here to stay.

The internet has slowly been shifting retail in the last 20 years, but that trend is accelerating. Understanding “under what circumstances does ‘in-person’ add value?” has become a key question well beyond retail. Just as physical retail and in person doctor visits will never disappear completely, travel will resume, and people will gather in bars, stadiums and convention centers. Finding the sweet spot, which changes over time, is tricky.

So where are those gorillas and how do we avoid missing them? As we look to the future, a wider view, for both risks, and opportunities may be the difference between success and failure. As Simon’s experiment showed, we alone may not perceive the gorilla, so an approach that takes many voices, perceptions, and viewpoints in next steps can help provide a broader understanding as to what your business looks like in the future.

Part 2: Seven New Ways of Changing Our Perceptions

“If you always do what you always did, you’ll always get what you always got.” This quote has been attributed to Henry Ford, Tony Robbins and a host of others. But in today’s environment what you always did may not be the outcome you desired. My previous post talked about missing those gorillas in our midst. Easier said than done, as we focus on those things we think will lead to our success. Until they don’t.

One advantage to this pandemic has been a flurry of ideas and articles to help business owners and managers change their views about past beliefs. OK, a wise person I know likes to say “the only person who likes change is a wet baby”. But here we are anyway. So here are a few tips to help you, even if change is not your thing:

Routines kill creativity:

In a study published in the journal Thinking and Reasoning, researchers Mareike Wieth and Rose Zacks reported that imaginative insights are most likely to come to us when we’re groggy and unfocused. Sleepy people’s “more diffuse attentional focus,” they write, leads them to “widen their search through their knowledge network. This widening leads to an increase in creative problem solving.” By not giving yourself time to tune in to your meandering mind, you’re missing out on the surprising solutions it may offer. So change up your morning or evening routines, and see if new ideas spring to mind.

Watch a Funny You Tube Video:

According to a study published in Psychological Science: “Generally, positive mood has been found to enhance creative problem solving and flexible yet careful thinking.” Subjects in the study who watched brief video clips that made them feel sad were less able to solve problems creatively than people who watched an upbeat video. A laughing baby video was much more helpful than the earthquake footage.

Read Something You Wouldn’t Normally Read:

Changing to a different topic in your reading pattern can spark new ideas. For example, University of Toronto researchers Maja Djikic and Keith Oatley concluded that, all other things being equal, people who read more fiction are also better at reading other people’s emotions. It’s not that empathic people read more, but that reading promotes empathy.

Talk to Someone Who Disagrees with you:

In an extreme example, in Malcom Gladwell’s book Outliers, he cites lack of confidence in challenging superiors led to Korean Air having numerous crashes. Because the co-pilots were culturally mandated to defer to their captains, they didn’t speak up and the results were literally deadly. Once Korean Air found out, they were able to address it and solve the problem. So perhaps your business issues are not deadly, but recall a fable where one VP, in congratulating another for being promoted to CEO said, “Congratulations, today is the last day anyone will tell you the truth”.

Aspire To Be the Dumbest Person in the Room:

Related to talking to someone who disagrees with you, author and career coach Sally Hogshead argues that if you are the smartest person in the room, you are not challenged or learning.

Learn Some History Lessons:

Adam Gopnik, author and columnist for The New Yorker argues that the absence of a historical sense encourages is presentism, in the sense of exaggerating our present problems out of all proportion to those that have previously existed. It lies in believing that things are much worse than they have ever been—and, thus, than they really are—or are uniquely threatening rather than familiarly difficult. Knowing history helps us to understand that human nature has not changed, and opens our minds to new solutions, and is perhaps is comforting as well. Having recently read Ron Chernow’s Alexander Hamilton, was amazed at the parallels in the political environment of the 1770’s and 80’s and our divided squabbling of today. And yet, here we are 240 years later.

Travel?

Nearly every article touts some variation on a change of scenery as a booster for fresh thinking and new insights. Of course today’s environment makes that effort a major challenge. However, the beauty of the internet is that virtually, the world is literally at your fingertips. Twelve museums around the world are open for visual tours: Maybe not the same as an in person visit, put perhaps an opportunity to consider a new destination or two for a post pandemic visit.

Vetting COVID-19 Data

Aristotle once postulated “horror vacui” (Nature Abhors a Vacuum). His expression certainly had relevance when COVID-19 came on the scene. In an absence of research about the virus, even the best minds in virology had to admit that they did not have all the answers.

In physics “vacuum” means “true empty space,” an environment with nothing in it. Into the vacuum, content providers worldwide rushed to fill the space. Much of what is filling the space is conjecture, speculation, and outright misinformation. So what is a person looking for useful information to do?

In his book, Factfulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong About the World – and Why Things Are Better Than You Think, Hans Rosling suggests:

Avoid Drama: If the basis of the content is emotion – a sad story, a scary narrative, or a shocking fact, know that the information reflects the bias or worldview of the author, not data. Training experts recommend that any lesson include stories, as people remember them more than straight information. If you must read these stories, know that you are not getting the full picture.

Do Some basic math: A fact in isolation can be scary. The Johns Hopkins Coronavirus dashboard splashed with red cirlces around the world, as of this writing, shows a million cases worldwide, a shocking number. However, with a world population of 7.8 billion people, this million represents 0.013% of the population. From April 12, 2009 to April 10, 2010, the CDC estimated there were 60.8 million cases (range: 43.3-89.3 million), 274,304 hospitalizations (range: 195,086-402,719), and 12,469 deaths (range: 8868-18,306) in the United States due ALONE to the H1N1 virus. Note that despite public health reporting, these ranges are huge – and much larger than current numbers. CDC estimated that about 500 million people, or one-third of the world’s population became infected with the Spanish Flu in 1918-1919 with at least 50 million deaths worldwide with about 675,000 in the US. Not that COVID-19 cases and deaths will not rise, but put the numbers in context of the broader picture for more realistic assessment of a situation.

Don’t play the blame game: Rosling says our hardwired instinct to find a guilty party in every situation derails our ability to develop a true, fact-based understanding of the world. When we obsess about who is to blame, it steals our focus and blocks out any learning we might gather from the negative experience. This undermines our ability to solve big problems in a more systematic way, or prevent them from happening again.

When you find information, know that reliable information always provides cross references, methodology, and sources. Always read the footnotes or follow the links to evaluate information. For example, the New York Times is publishing a detailed US map showing the number of cases at https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-us-cases.html – methodology at https://github.com/nytimes/covid-19-data. The methodology notes that each health department referenced provides information differently, and that counts can rise or fall even within the space of a few days. The information is reasonably reliable, but shortcomings and potential errors are also fully disclosed.

Bottom line, information is changing rapidly. Professor Neil Ferguson, Director, MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis, Imperial College London, was a primary source relied on by many policymakers and governments for a model that suggested 2 million US deaths from COVID-19. Ferguson’s model is now being challenged by the Oxford model. Both models, while mathematically sound, rely on past data, some of it likely faulty. Oxford’s model assumes greater spread of the virus prior to its detection, thus increasing the likelihood of herd immunity. Even the experts continue to revise and change information. However, credible sources with the latest information will always:

- Reference respected medical publications, such as The Lancet, New England Journal of Medicine, or other peer-reviewed journals. Peer-reviewed journals are publications in which scientific contributions have been vetted by experts in the relevant field. Peer-reviewed work isn’t necessarily correct or conclusive, but it does meet the standards of science. For example, https://theconversation.com/the-coronavirus-looks-less-deadly-than-first-reported-but-its-definitely-not-just-a-flu-133526 references respected journals such as Nature Medicine, The Institute for Disease Modeling, and The Centre for the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases. However, it was last revised on March 22, so recognize that newer the date, the more reliable in this rapidly changing environment. Consumer Reports’ FAQ https://www.consumerreports.org/coronavirus/coronavirus-faq-what-you-need-to-know-covid-19/, is updated frequently, and references JAMA (Journal of the American Medical Association), New England Journal of Medicine, the CDC, and other reputable sources.

- Include a methodology that notes both the way the information was gathered and the potential shortcomings of the data presented, such as the New York Times map noted above. While frequently referenced, the Johns Hopkins worldwide map does not provide a full explanation to underpin the accuracy of their reported numbers.

Context and back story matter. When looking at case reporting, always look for ways to ‘do the math’. Data from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation shows that New York only has 13,010 hospital beds (718 ICU) for 20 million people; less than one bed per 1,000 people. Missouri has 7,933 beds and 558 ICU beds for a population of 6.2 million. So the problem is a resource allocation issue as much as a disease issue. The World Bank estimates put Italy’s number of Hospital beds per 1,000 population at 3.4 – compared to 8.3 in Germany, while Italy’s average age of the population is one of the oldest in Europe. About 24% of Italy’s population is 65 or older, compared to 22% in Germany, and 16% in the US.

These are uncertain times, but having the most accurate and up to date information will help you to assess the situation in the most realistic way. And of course, wash your hands! This is one thing the experts DO seem to agree upon.

Looking Beyond the Headlines

For 11 years, I was the managing director for the Kansas City Manufacturing Network, which provided educational and networking opportunities to the region’s manufacturing company owners and managers. While I have moved on from that role to better focus on my research business, I am still passionate about the makers, doers and builders that underpin a vibrant economy.

I was recently contacted by a reporter asking me about reaction to a story that the region had experienced a net job loss of 1,900 manufacturing workers. I could not help but note that this fact in isolation does not necessarily make a headline in and of itself, without taking the context of the bigger picture into account.

First, manufacturing is not monolithic. Manufacturers in this region produce products as diverse as the heat resistant bag holding your rotisserie chicken, to the components used in the manufacturing of the automobile you drive. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s September Manufacturing Survey reported that nearly 34 percent of regional manufacturing contacts indicated that their number of expected employees for 2019 was higher since the beginning of the year, while 25 percent had lowered expectations for 2019 employment levels. Tariffs, global uncertainty and declining capital expenditures in some sectors have hurt some, while others report continued strong order volume and growth.

Second, the demographics of the manufacturing workforce are rapidly changing. A July 2019 study, The Aging of the Manufacturing Workforce: Challenges and Best Practices, published by the Manufacturing Institute, notes that as of 2017, nearly one-quarter of the sector’s workforce are age 55 or older. Almost all (97 percent) survey respondents in this study report being aware of the issue, and the vast majority (78 percent) indicate that they are very or somewhat concerned about this change. Workers shed in one sector are often quickly absorbed into other more vibrant sectors as looming retirements are gutting the production floor in many plants.

Labor analysis by Mid-America Regional Council in January 2019 concurs. The region has seen greater employment growth in manufacturing than the US as a whole every year since 2014. However, this sector employs fewer workers under the age of 25 relative to the metro average, while those 45 to 54 are the most over-represented. Opportunities abound, but students are not aware of them. K-12 schools aren’t fostering critical skills, and skilled workforce programs struggle to fill seats in classrooms. A series of student surveys and focus groups showed that 93% of the region’s students had little or no information about jobs or opportunities in the skilled trades.

Yes, in manufacturing, like in many industries, shift happens. Durable goods sectors are vulnerable during economic downturns. Automation is taking some jobs, but more are being created. Shortages of programmers and maintenance technicians are common, and automation advances have made many advanced manufacturers competitive with overseas suppliers, bringing jobs back to the US, or keeping those that would have been otherwise lost. Despite well-publicized employment declines of the last 2 decades, the US employs 16.4 million workers who produce 18% of the world’s manufacturing output, valued at $1.867 billion. This output is second only to China, just over $2 Billion in output, produced by 128 million workers. Obviously, US manufacturing is much more productive. So yes, the region’s loss of 1,900 jobs is concerning, but certainly, don’t write off our region’s manufacturers.

Context Matters

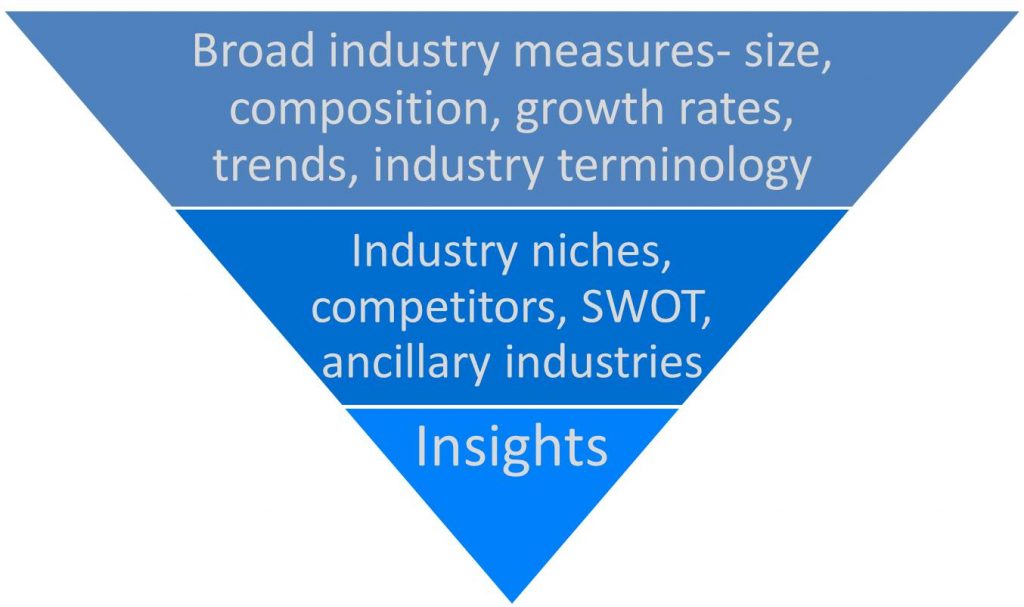

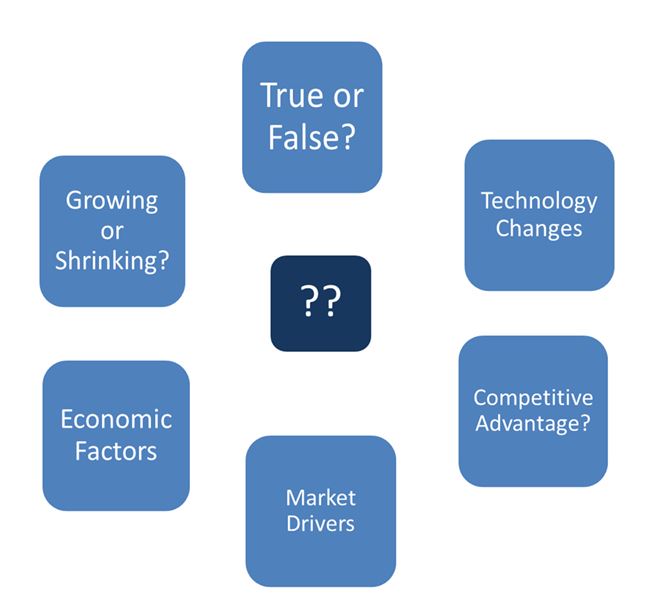

I recently was asked if I could specifically locate insight on how a customer segment made purchase decisions in the interior design industry. I call these kinds of projects ‘fetch’ projects and typically, I don’t do them. Why? Because fetch has no context. In 25 years of doing research, I have found that the best insights come from a broad, complete picture how that insight fits into a bigger picture. I call this process the ‘Research Funnel’

In the case of the customer purchase decision, I started with the broader industry measures. Interior design is a fragmented market. There are no 600 pound gorilla firms, no public companies, and even typically reliable sources vary in the number of designers currently working in the field. Typically, insights are fuzzier in such markets, and smaller, nimbler firms can change rapidly, so keeping a pulse on trends is more important vs slower to change markets with large public companies. Nationally, the average count is 57,000 designers, but this also varies significantly from state to state. This number has grown steadily since the recession, indicating both growth in the industry, and growth in competition. At a first glance, the primary drivers are new construction, and remodeling, both of which are in growth mode, but several sources note that growth is slowing, and varies by region.

The other driver, less mentioned, is consumer confidence in their own design choices. There is a segment of the population who will always hire a designer – for status, expedience, or to ensure that their space conveys their personal or corporate brand. But the design industry, like many others, is changing due to online competition, supply chain changes, and new technology. Growing competition, arises from retailers moving upscale with more sophisticated design resources (RH, Crate & Barrel), offering complimentary design services (Ethan Allen, Pottery Barn, West Elm), and emerging new-age internet etailers and services (Wayfair.com, Havenly.com). Some furniture manufacturers are dabbling with going directly to consumers, with new 3D visualization technology that allows customers to virtually place pieces in their home. Mass merchants such as Home Depot are offering design assistance, either online or in person. Bottom line, these changes are helping customers feel more confident in their ability to make design decisions.

National surveys of designers indicate cost pressures and shrinking margins. In a market where pricing pressures are also increasing, leading designers have increased emphasis on marketing, especially marketing the value that they bring to their customers. An effective design process ensures that the space works for the intended need, avoids costly changes later, and increases overall satisfaction with the space. As services like Pinterest, Instagram, and Houzz spawn lookalike interiors, upscale clients will increasingly look to designers to create one of a kind environments, and specialized services. Some even handle the entire moving process, from designing the new space, to coordinating the move, so the client just has to pick up the keys and walk in to a completely furnished and unpacked residence.

However, even among the top-tier wealthy clientele segment, there are differences by generation. Millennials tend to value convenience, and a focus on experience rather than things, relative to other generations. A survey by Furniture Today noted a host of factors that their respondents consider when looking to hire a designer – with Service, Experience, Reputation and Cost cited by 80% or more respondents. So perhaps, “How do wealthy prospective clients make the decision to hire a designer?” is a simple question. But the answer, like most questions, is complicated. The broader context matters.

Why Do I Need a Researcher?

When my daughter was a teenager, you know, those years when they know everything, she remarked, Mom, with Google out there, why would anyone need to hire you? I initially laughed, but she had a point. Most of us have become pretty adept at finding information on the fly. But when it comes to critical decisions in your business, sometimes Google can be equal parts friend and enemy.

- There’s confirmation bias. Whether we realize it or not, we tend to gravitate towards information that confirms what we are already thinking. Sometimes, bringing in a 3rd party with no opinion can uncover angles you had not previously considered.

- There’s overload. A generic search can literally produce over a million results. Are the first 10 the most accurate? For business information, there are a plethora of sources that are more targeted and accurate than what Google, or any search engine, chooses to show you in the top results. It’s a start, but certainly not the best way to gather quality data.

- There are inaccuracies. In a recent project, 5 sources gave 5 different estimates for the size of the industry. Which one is correct? Sources matter, and digging into what assumptions are behind the estimates, forecasts, and projections helps provide deeper understanding and proper context.

- There’s time. “I have too much free time”, said no one ever. Business changes with increasing speed, and keeping up is always a challenge. Temptation to do a quick review and move on can mean incomplete or incorrect information, which can create blind spots that can cost you both time and money.

If you are facing questions, and need answers, you can go it alone. But if you are looking for an objective perspective, need to save time, or just not sure which direction to go, a researcher can save you both time and money.

What are your assumptions?

Whether you are a city planner, a CFO, or a company owner, you likely have developed plans based on a future state. The way we look at the future from a financial, or allocation of resources standpoint, is primarily based on what our assumptions of what the future will look like. Sometimes, the traditional wisdom bears further examination.

Take the often quoted assumption that Millennials are not home buyers. This assumption was central to a housing study commissioned by the city of Lee’s Summit in 2017. However:

- Highline, a real estate marketing firm conducted a housing survey of Kansas City Millennials, published in the Business Journal on January 3, 2018. Five years from now, the majority of respondents want to live somewhere other than Downtown, with many saying they would be looking for neighborhoods in suburban areas that are safe and have good schools. Seventy-four percent said they wanted to buy, not rent, their next place.

- Locally: The South Kansas City Alliance surveyed future workers at the planned 290-acre Cerner campus at Interstate 435 and 87th Street to find out what future workers there would like to see. The survey garnered roughly 600 responses, with two-thirds of those respondents age 35 or younger. Of the respondents:

- 66% currently own their single family residence

- 75% expected to be living in a single family home in the next 5 years

- 41% responded that they were ‘very likely’ to move within the next 5 years, and of those respondents, 69% expressed interest in a home that was either new or less than 10 years old.

Cerner anticipates employing 16,000 workers at the South Campus by 2026.

Even if there is growing demand for multi-family in the metro, Lee’s Summit is not an island. Part of demand assumptions need to factor in location preferences and what else is offered throughout the region. Highline’s Millennial Housing Preference study in 2019 asked both renters and homeowners where they wanted to live next. The five most popular neighborhoods for renters, in order, were the River Market, Midtown, Brookside/Waldo, the Crossroads and the Country Club Plaza. Study authors note that Older millennials are starting to age out of renting and looking to buy, something that bucks the larger, national narrative about the generation.

Fannie Mae’s Multifamily Metro Outlook for Kansas City in 2018 noted 130,000+ rental units in the Metro, with 6200 more under construction, 12,700 in the planning process, a total increase of >10%.

The 2019 Outlook for the first half of 2019: 7,700 units underway and 10,000 units in the planning stage. While Fannie Mae notes this increase as ‘modest’ 7,700 units in a conservative estimate of 130,000 existing units, this represents an almost 6% increase in capacity. According to Mid-America Regional Council, the region’s net population growth from 2016-2017 was only 1.1%, or a 20,000 person increase. A 2019 release notes that the Kansas City metro area added 16,392 new residents from 2017-18. How many of those are prospective renters vs owners? The increases and decreases vary a lot from area to area – from 6800 new residents in Kansas City, MO, to a net loss of 59 residents in Raytown, MO. Location matters.

Fannie Mae’s report also provides data from 3 sources: CBRE-Econometric Advisors, CoStar and Reis, Inc. All 3 sources – different totals, different absorption, vacancy and completion data. All 3 sources are credible. Why the differences? Assumptions. In order to really understand the numbers, it’s important to look at your information sources’ assumptions behind their data, as they always will influence the results.

Bottom line: Even if you have credible data, from a credible source, don’t assume you have all the answers you need when making a decision. Make sure you also understand the assumptions behind the data you are relying on, if you truly want to make an informed decision.